Cancer

Cancer Prevalence Across Ethnicity-Education-Deprivation Subgroups: An Intersectional Analysis Vladimir Jolidon* Vladimir Jolidon Bernadette WA van der Linden Stefano Tancredi Andrew Bell Daniel Holman

Background: Identifying variation in cancer prevalence across population subgroups is critical for public health. Previous research has shown that cancer prevalence is lower among non-White ethnic groups compared to White ethnic groups in England. However, these studies relied on broad ethnic categories and overlooked the intersection of ethnicity and socioeconomic position. The present study examines cancer prevalence across more specific ethnicity-education-deprivation subgroups from an intersectional perspective.

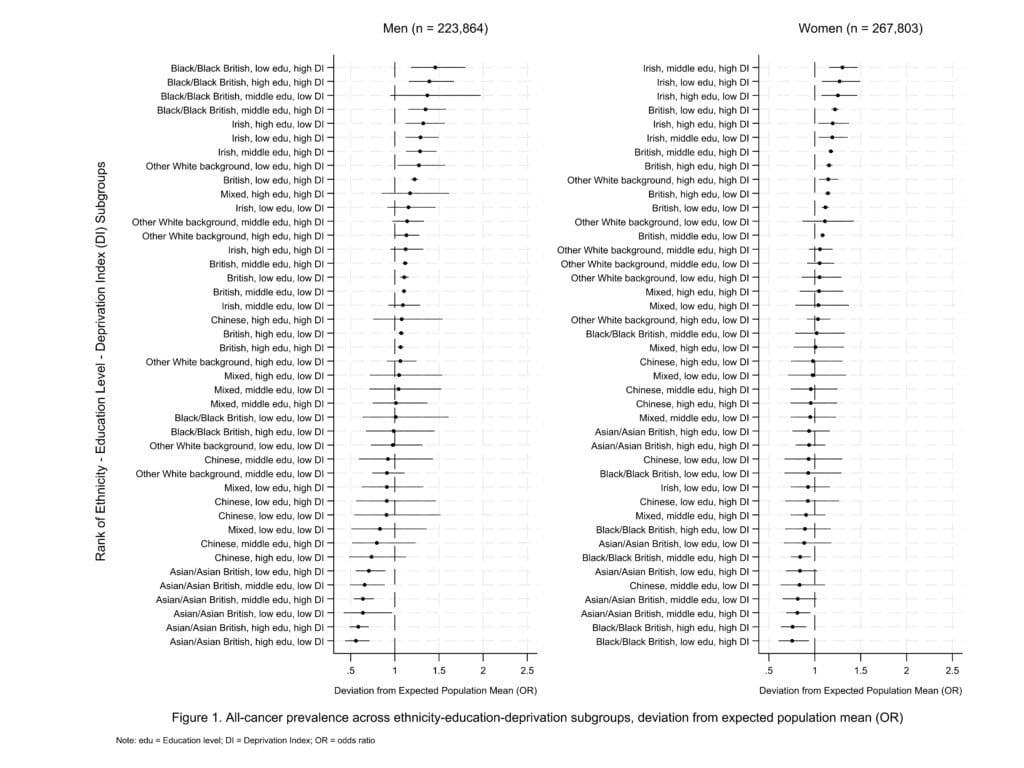

Methods: Data from the UK Biobank, a prospective cohort study, included 267,803 women and 223,864 men aged 40-69 years old at baseline. The outcome was all cancer prevalence, excluding non-melanoma skin cancer. Multilevel analysis of individual heterogeneity and discriminatory accuracy (MAIHDA) was conducted, nesting individuals within 42 subgroups based on seven ethnic groups, three education levels (low, middle, high), and two deprivation levels (low, high), stratified by sex and adjusted for age.

Results: Overall, cancer prevalence was 14.6% among women and 16.3% among men. As in prior studies, cancer prevalence was generally lower in Non-White groups. However, ethnicity-education-deprivation subgroup analysis highlighted key differences. Among men, Black subgroups had the highest cancer prevalence, especially in groups with lower education and higher deprivation levels. Among women, cancer prevalence was highest among Irish and British subgroups with lower education and higher deprivation levels. MAIHDA models revealed that between-group differences were additive rather than multiplicative.

Conclusions: This study highlights disparities in cancer prevalence across intersectional subgroups, revealing patterns that are often masked by ethnicity-only analyses using broad categories. Identifying subgroups at higher risk of cancer can inform targeted interventions to address inequities in cancer prevention and care.