Aging

Lifecourse Socioeconomic Position and Cognitive Function: Leveraging Intergenerational Data from the Framingham Heart Study Ruijia Chen* Ruijia Chen Chang Su Phillip Hwang Maria Glymour Andrew Stokes

Background: Parental socioeconomic position (SES) is linked to cognitive function, but many studies relied on offspring-reported parental SES, which is prone to recall bias, and used models inappropriately adjusted for potential mediators across life stages. Using multigenerational data from the Framingham Heart Study (FHS), we fitted marginal structural models to assess the associations of lifecourse SES with cognitive function and decline.

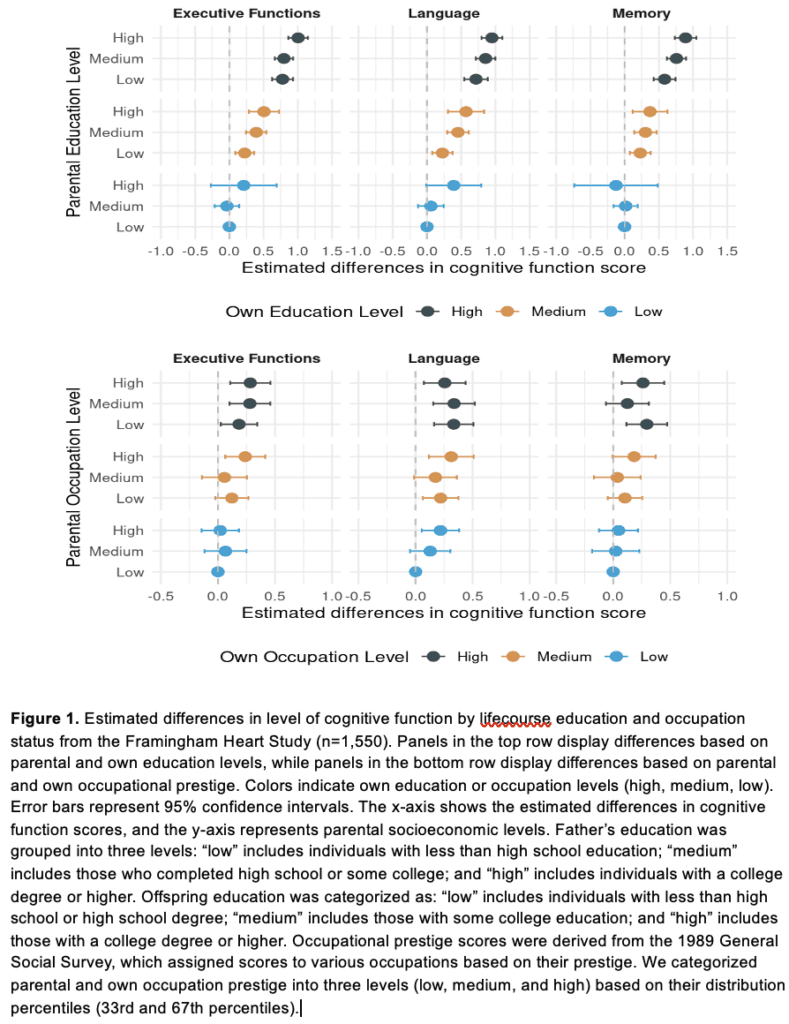

Method: Data are from the 1992-2018 FHS Offspring Cohort, with parental SES derived from the Original Cohort. Own and parental education were assessed by the highest level of education achieved; occupation was based on either current or most-recent pre-retirement occupation. Parental and own education and occupation were classified into high, medium, and low categories (see Figure 1 note for detailed grouping criteria).Executive function, language, and memory were used as outcomes in linear mixed-effects models with random intercepts. Inverse probability weights were used to account for treatment-confounder feedback loop and loss to follow-up.

Results: Among 1,550 participants (mean age: 60.4 years, SD = 9.7; 52% women), cognitive function showed a strong gradient with own education, more than with parental education. For example, participants with high parental and own education scored 1.00 SD (95% CI: 0.86, 1.15) higher executive function than those with low parental and own education. Those with high parental and medium own education scored 0.51 SD higher (95% CI: 0.29, 0.73), while high parental and low own education showed weaker associations (0.21 [95% CI: -0.27, 0.70]). Occupational gradients were less pronounced. Neither parental nor participants’ own SES was associated with cognitive decline over an average of 9.5 years of follow-up.

Conclusions: Both parental and own education contributed to cognitive health in later life, with participants’ own education playing a more important direct role than parental education.