Perinatal & Pediatric

Gestational weight loss or gain and offspring growth in infancy and childhood: differences by trimester and pre-pregnancy BMI Anna Booman* Janne Boone-Heinonen Dang Dinh Anna Booman Byron A Foster Erin LeBlanc Natalie Rosenquist Rachel Springer Evelyn Sun Kimberly K Vesco

Background: Higher gestational weight gain (GWG) is well known to be associated with higher offspring body mass index (BMI), but less is known about associations with early childhood growth patterns that lead to high childhood BMI, especially in higher pre-pregnancy BMI groups.

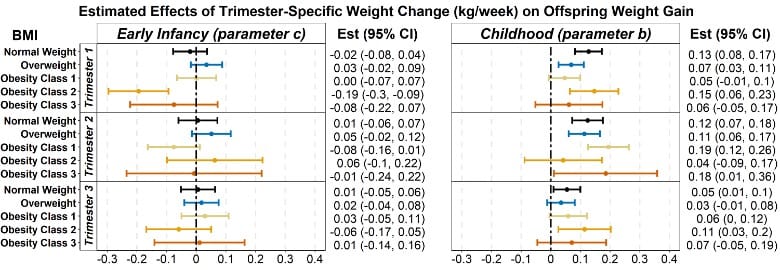

Methods: We examined 18,228 children born to pregnant people receiving care from a national network of community health centers. We estimated nonlinear growth during infancy and linear growth in childhood using the Jenss model (birth to 5 years of age). In pre-pregnancy BMI-stratified analysis (normal weight, overweight, obesity class I, II, III), we calculated trimester-specific weight change using latent piecewise trajectory models, then modeled infancy (~0-12 months) or childhood (~12 to 60 months) weight gain parameters as a function of trimester 1, 2, or 3 GWG rate and maternal characteristics using linear regression.

Results: In general, higher trimester-specific GWG rates were not associated with early infancy weight gain, particularly in children of birthing parents with pre-pregnancy normal weight through obesity class I [range of estimates (95% CI): -0.08 (-0.22, 0.07) to 0.05 (-0.02, 0.12)]. In contrast, GWG was associated with faster childhood weight gain [range of estimates (95% CI): 0.03 (-0.01, 0.08) to 0.19 (0.12, 0.26)]. Notably, findings were mixed for pre-pregnancy obesity class II and III groups: for example, for obesity class II, trimester 1 GWG was associated with slower early infancy weight gain followed by faster childhood weight gain. In general, associations were stronger for trimester 1 and 2 than for trimester 3 GWG.

Discussion: Higher GWG in early pregnancy may lead to higher child BMI via faster growth in childhood, rather than in infancy. Given that rapid growth in infancy is more strongly linked to future risk of diabetes and other conditions, these findings suggest a need to understand the long-term impacts of GWG-induced childhood weight gain.