Structural

The association between structural racism and Black-White health inequities in major causes of death and life expectancy in the United States, 2019-2021 Corinne A Riddell* Corinne Riddell Elleni Hailu Stephanie Veazie Mathew Kiang

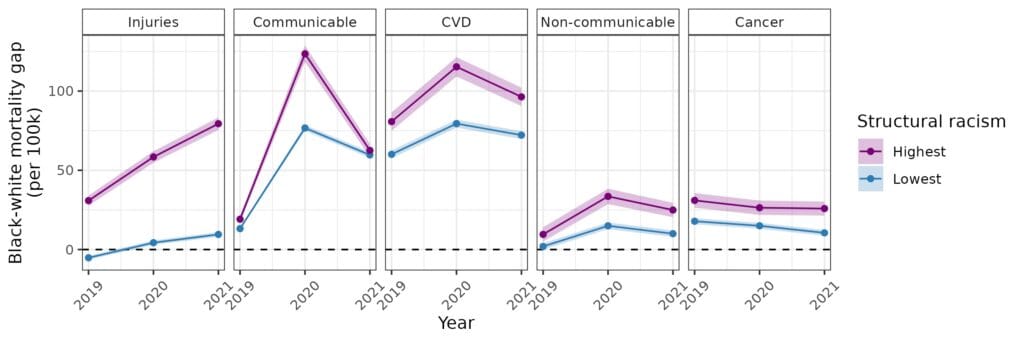

We examined the association between state-level structural racism and Black-White health inequities in 2019, 2020, and 2021. We used data from the American Community Survey and the Bureau of Justice Statistics to measure Black-White relative disparities in education, income, homeownership, employment, and incarceration for 2015-2019 in each state. The measures were input into a latent profile analysis to cluster states into five typologies of structural racism. We calculated age-standardized cause-specific mortality rates by race, in each year for each typology of structural racism. We then calculated the absolute difference in mortality rates between Black and White individuals (hereafter “mortality gap”). In 2019, states in the highest structural racism typology had a larger Black-White mortality gap compared to states in the lowest structural racism typology, especially for injuries (See Figure; Low structural racism [SR]: -5 per 100k; High SR: 31 per 100k) and cardiovascular diseases (Low SR: 60 per 100k; High SR: 81 per 100k). In 2020, the Black-White mortality gap increased for all causes except cancer for high and low structural racism typologies. This increase was larger for states with high structural racism. The most disparate increase was for communicable diseases (Low SR: 77 per 100k; High SR: 124 per 100k). In 2021, the mortality gap increased for injuries, but narrowed for communicable diseases and CVD. As a result of the mortality gap, from 2019 to 2021, disparities in Black and White life expectancy widened everywhere, but more in high vs. low structural racism (2019 for men: Low SR: 3.8 years, High SR: 6.2 years vs. 2021: Low SR: 4.9 years vs. High SR: 9.0 years). Patterns highlight the link between structural racism and racial health disparities. The dynamic shifts in health outcomes suggest inequities are not static and racial health equity can be achieved by addressing underlying differences in wealth, opportunity, and power, which shape health.