Injuries/Violence

Timing of First Sexual Violence Victimization in Young Adults: Variations by Sexual and Gender Characteristics Xiyuan Hu* Xiyuan Hu Mary Ryan Baumann Mariétou Ouayogodé

Introduction

Sexual violence inflicts profound and enduring negative impacts on victim’s health and quality of life. Research has documented that sexual violence significantly increases the risk of serious mental health conditions, substance use, lower education attainment, and reduced employment opportunities. The risk of experiencing sexual violence varies across sexual and gender characteristics (SGC), with females and non-heterosexual individuals facing disproportionately higher rates of victimization.

In this research, we examined the relationship between SGC and the timing of first exposure to sexual violence among young adults in the United States (US), distinguishing between physical and non-physical forms. Physical sexual violence encompasses any unwanted sexual activity involving physical contact, whereas non-physical sexual violence includes unwanted sexual acts that occur without direct physical contact. To our best knowledge, it is the first study to assess the relationship between SGC and the timing of sexual violence victimization for such a large cohort.

Method

Data Sources

The dataset comes from Add Health, The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, which was initiated in 1994. Add Health is a nationally representative school-based panel study of adolescents from grade 7 through 12 in the US. The cohort was tracked throughout young adulthood by four in-home interviews.

Add Health is the largest and most extensive longitudinal survey of adolescents. It collects longitudinal data about respondents’ demographic, social, economic, psychological, and physical well-being along with contextual information on people and their communities. The data is divided into five waves, with Wave I occurring in September 1994-December 1995, Wave II in April-August 1996, Wave III in August 2001-April 2002, Wave IV in 2008-2009, and Wave V in 2016-2018.

In Wave IV, participants reported the dates and circumstances of significant life events during young adulthood, including experiences of both physical and non-physical sexual violence. In the present analysis, we used Wave IV data to examine the relationship between SGC and experiences of sexual violence, encompassing both physical (N = 4,816, events = 417) and non-physical (N = 4,811, events = 609) victimization.

Variables

The dependent variables were the timings of first victimization for both physical and non-physical sexual violence. Physical sexual violence was assessed through two questions: “Have you ever been physically forced to have any type of sexual activity against your will? Do not include any experiences with a parent or adult caregiver” and “How old were you the first or only time this happened?” Non-physical sexual violence was similarly measured using two questions: “Have you ever been forced, in a non-physical way, to have any type of sexual activity against your will? For example, through verbal pressure, threats of harm, or by being given alcohol or drugs? Do not include any experiences with a parent or adult caregiver” and “How old were you the first or only time this happened?”

Sexual orientation was determined through self-identification. Participants who identified as “100% heterosexual (straight)” or “Mostly heterosexual, but somewhat attracted to same sex” were classified as heterosexual. Those who identified as “Bisexual, that is, attracted to men and women equally”, “Mostly homosexual, but somewhat attracted to opposite sex”, “100% homosexual (gay)” or “Not sexually attracted to either males or females” were classified as non-heterosexual. By combining sexual orientation with biological sex, participants were categorized into four SGC groups: heterosexual males, heterosexual females, non-heterosexual males, and non-heterosexual females.

Statistical Analysis

Given our focus on examining both the occurrence and timing of initial sexual violence victimization across different SGCs, survival analysis was determined to be the optimal analytical approach. Specifically, Cox proportional hazards regression was employed to estimate the hazard ratio of sexual violence victimization among different SGC groups.

The analysis controlled for several potential confounding variables: race (White (the reference), Black or African America, American Indian or Alaska Native, or Asian or Pacific Islander), education (less than high school (thw reference), high school, some college, college, more than college), and personal annual income.

We first presented descriptive statistics of the study population. Then, we examined the timing of first victimization for both physical and non-physical sexual violence using Kaplan–Meier survival estimates and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models. The risk period for sexual violence victimization was considered to begin at birth. For respondents who reported having experienced sexual violence, the age at first victimization was recorded as the event time. Respondemts who reported no sexual violence experiences were right-censored at their age during the Wave IV interview.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The mean age of participants was 29 years old. The sample was predominantly white (72%) and heterosexual (95%), with most participants having completed some college education (76%). Income levels varied by group, with heterosexual males reporting the highest income, followed by non-heterosexual males and heterosexual females, while non-heterosexual females reported the lowest income.

Among participants who experienced sexual violence, the mean age at first physical and non-physical sexual violence victimization was 16 years. Physical sexual violence was reported by 9% of the total sample, with disproportionately higher rates among non-heterosexual and heterosexual females. Among those who experienced physical sexual violence, heterosexual males reported the earliest mean age of victimization at 11 years. Non-physical sexual violence was reported by 13% of the sample, again with higher rates among non-heterosexual and heterosexual females. However, among those experiencing non-physical sexual violence, non-heterosexual females reported the earliest mean age of victimization at 13 years.

Timing of first physical sexual violence victimization

Kaplan-Meier survival estimates indicated higher hazards of physical sexual violence among non-heterosexual and heterosexual females compared to heterosexual males. Non-heterosexual males showed slightly elevated risk compared to heterosexual males. The log-rank test revealed significant differences between at least one of the four groups (χ² = 251, p < 0.001).

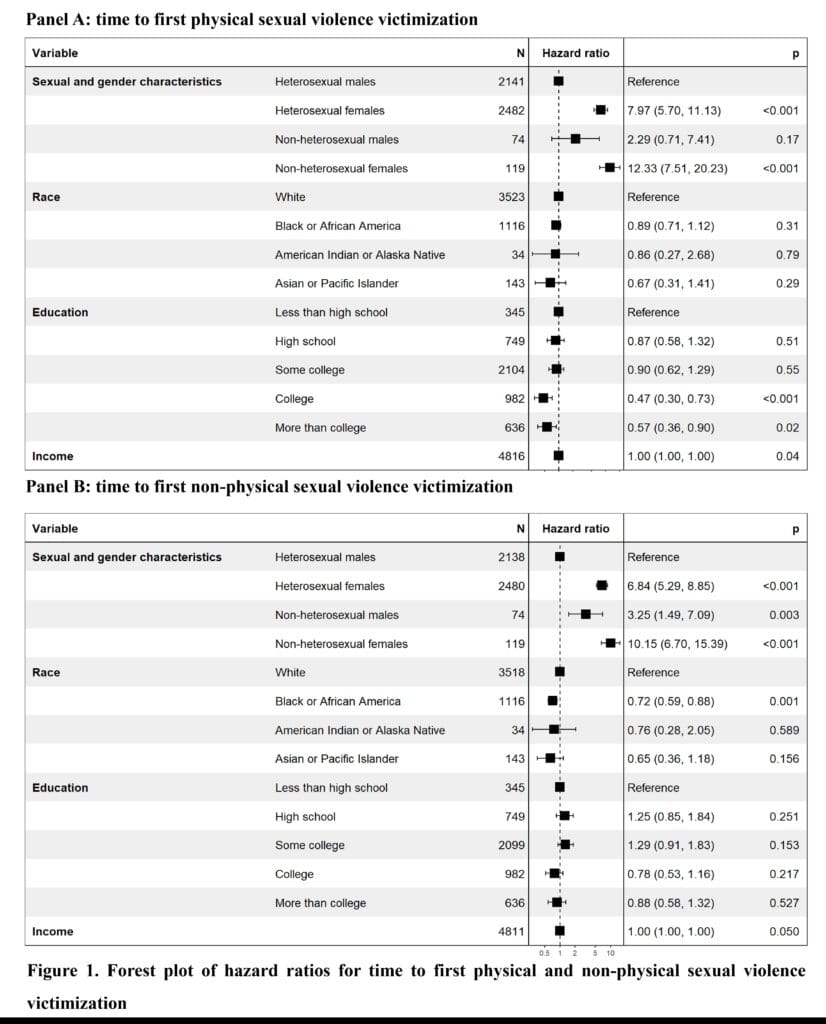

The Cox proportional hazards regression models examined the association between SGC and time to first physical sexual violence victimization, adjusting for confounding factors (Figure 1). Compared to heterosexual males, non-heterosexual females exhibited the highest relative risk, with a hazard ratio of 12.33 (95% CI: 7.51, 20.23). Heterosexual females showed a hazard ratio of 7.97 (95% CI: 5.70, 11.13) relative to heterosexual males, controlling for race, education, and income. Non-heterosexual males revealed a marginally elevated hazard ratio of 2.29 (95% CI: 0.71, 7.41) compared to heterosexual males, all else held constant, though this was not statistically significant.

However, the Schoenfeld residual test indicated a violation of the proportional hazards assumption for both the SGC variable (χ² = 35, p < 0.001) and the overall model (χ² = 46, p < 0.00

Timing of first non-physical sexual violence victimization

Kaplan-Meier survival estimates revealed elevated risks of non-physical sexual violence among all groups compared to heterosexual males, including non-heterosexual females, heterosexual females, and non-heterosexual males. The log-rank test showed significant differences between at least one of the four groups (χ² = 324, p < 0.001).

Cox proportional hazards regression models examining the association between SGC and time to first non-physical sexual violence victimization, with adjustment for confounding factors (Figure 1), revealed substantial group differences. Non-heterosexual females were found to have the highest relative risk, with a hazard ratio of 10.15 (95% CI: 6.70, 15.93) compared to heterosexual males. Heterosexual females showed a hazard ratio of 6.84 (95% CI: 5.29, 8.85) relative to heterosexual males, controlling for race, education, and income. Non-heterosexual males exhibited a hazard ratio of 3.25 (95% CI: 1.49, 7.09) compared to heterosexual males, all else held constant.

However, the Schoenfeld residual test indicated a violation of the proportional hazards assumption for both the SGC variable (χ² = 10, p = 0.021) and the overall model (χ² = 30, p = 0.002).

Discussion

We found that non-heterosexual females had the highest risk of experiencing both physical and non-physical sexual violence victimization compared to heterosexual males. Heterosexual females also faced significantly higher risk of experiencing both forms of sexual violence victimization compared to heterosexual males. Additionally, non-heterosexual males were at significantly higher risk of experiencing non-physical sexual violence victimization compared to other sexual and gender groups. While non-heterosexual males also showed an elevated risk for physical sexual violence victimization, the result were not statistically significant. Consistent with the prior research, these findings highlight the disproportionately high burden of sexual violence among certain sexual minorities and gender subgroups.

The findings have important implications. Childhood and adolescent sexual violence has long-lasting and detrimental influences on an individual’s well-being. Females and non-heterosexual individuals, already facing systemic disadvantages, may be particularly vulnerable to negative consequences of such violence. Therefore, prevention and protection programs targeting children and adolescents should prioritize addressing the specific need of females and non-heterosexual individuals.

Limitations

The findings in this study should be interpreted with caution considering several limitations. First, participants may have been clustered at the school and state levels, but the study did not account for this potential clustering factor. Second, the impact of SGC on the timing of sexual violence victimization may vary over time; incorporating time-varying coefficients may better capture the potential dynamic effects. Third, the study’s SGC classification was simplified due to limited access to gender identity data, preventing analysis of non-binary and other gender identities. Fourth, the study may be subject to residual bias from uncontrolled confounding factors like family socioeconomic status and community environments. Fifth, conclusions are based on data from young adults aged 25 to 34 in 2007-2009 and may not be generalizable to other age groups or more recent cohorts. Lastly, the findings may be affected by measurement bias, as individuals—particularly male participants—may underreport experiences of sexual violence due to social stigma and gender-based expectations around victimization.

Conclusion

Both non-heterosexual and heterosexual females were at a higher risk of experiencing physical and non-physical sexual violence victimization compared to heterosexual males. Non-heterosexual males also faced a heighted risk of experiencing non-physical sexual violence victimization. To mitigate the enduring consequences of sexual violence, prevention and protection services should prioritize interventions for females and non-heterosexual individuals during childhood and adolescence.